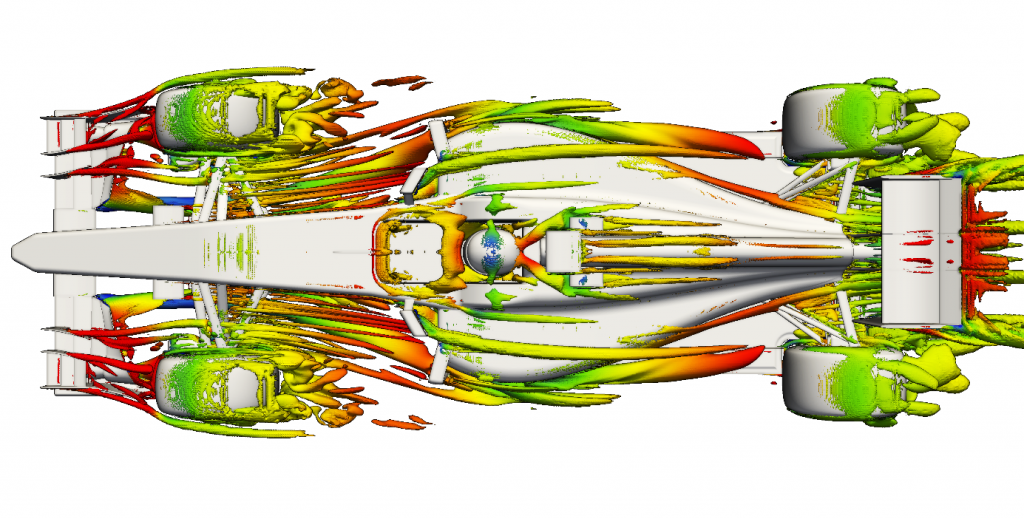

With all due respect to the many safety improvements that have been made, the biggest change to race cars over the past 50 years is surely the addition of wings, spoilers, splitters, and other devices that harness downforce and help the cars go through corners faster.

By the 1960s, as racing tires became capable of handling a greater cornering load, clever designers like Colin Chapman began to equip their cars with wings to provide aerodynamic grip and push the cornering speeds higher still.

Since then, those aero devices have found their way onto nearly every race car around the world, with designers routinely exploiting gray areas in the rulebook to add more downforce wherever possible. Even this year, a handful of Formula 1 teams added “T-wings” in front of the rear wings for an extra aerodynamic gain.

Depending on your perspective, discovering and harnessing downforce is either a triumph for innovation and fluid dynamics, or a competition-crushing scourge on motorsports that can’t be unlearned or undone.

Trust…

Okay, maybe that’s a bit extreme. But I am somewhat wary of downforce, largely because my driving style isn’t well-suited for high-downforce cars. I described one reason in the first post of this series: my early braking is inefficient in cars that can be driven deep into a corner. Another reason has to do with a quirk of downforce itself.

Wings, spoilers, diffusers, and the like don’t do anything when you’re sitting still. They only produce downforce at speed. And as speeds increase, downforce increases by the speed squared. So if you can carry more speed into a corner, the downforce will be much higher, which keeps the car even more planted.

While I understand this concept, actually putting it into practice has always been tough for me. During preparations for my first 24-hour race at Spa driving the McLaren MP4-12C, my teammates had to repeatedly talk me into lifting less and carrying more speed through the fast Blanchimont turn since the extra downforce would actually make the car more stable.

At least for me, trusting these unseen factors, even in a racing sim, is akin to blindly falling into the arms of someone behind you. Even if you believe that they’ll catch you, how hard are you actually willing to fall?

…but Verify

To get more insight into driving with downforce, I talked to my friend and teammate Dean Moll, who enjoys driving high-downforce cars and has lots of experience in prototypes and open wheelers. Growing up in Indiana, Dean said the Indy 500 guided his sim racing progression, including both the old Dallara IRL05 and new DW12 Indy cars in iRacing.

Dean started our conversation by assuring me that he’s no expert on driving with downforce, but he’s certainly more of one than I am. As proof, I witnessed him put in one of the greatest drives I’ve ever seen in last year’s Daytona 24 Hours, pushing our Daytona Prototype as hard as he could lap after lap en route to a narrow win.

That uncanny ability to consistently find the limit under braking is one thing I’ve always struggled with, which is another reason why I’ve generally stuck with a slow-in, fast-out style. But even Dean said it was an acquired skill for him.

“It did not come naturally at first, but my driving style evolved over time to prioritize mid-corner speed,” he told me. “My approach in practice is to keep moving my braking point deeper into the corner while applying the same amount of braking until I can no longer make the corner exit without pushing wide.”

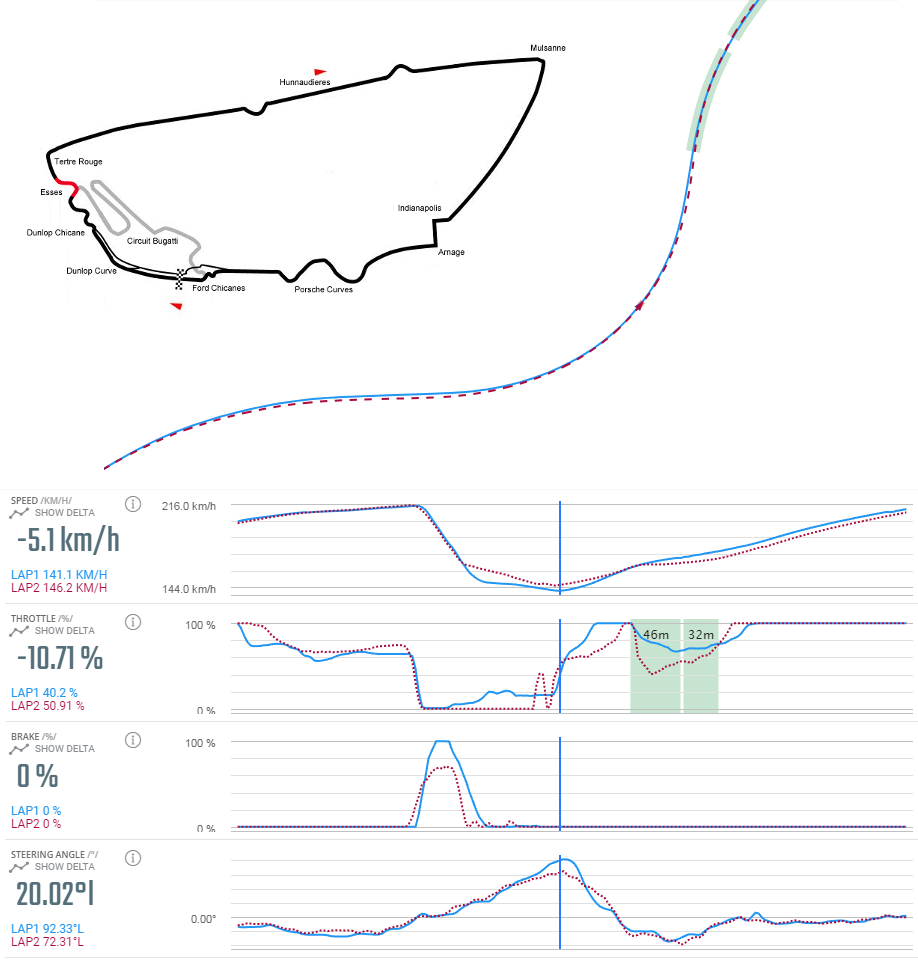

Even outside of a high-downforce car, those same traits show up in Dean’s driving style. Compare each of our fastest laps from the NEO Endurance Series’ 24 Hours of Le Mans race earlier this year driving the Mercedes AMG GT3.

Entering the esses, Dean stayed farther to the right than me, allowing him straighten the braking zone. He also used less steering input; by the middle of the corner, my steering angle was 20 degrees greater than his. This approach allowed him to carry about 5 km/hr greater mid-corner speed.

The advantage of my style — the fast out part — kicked in exiting the corner. I was able to get back to the throttle sooner than him, and his bigger lift off the throttle over the exit kerbs meant I was a bit faster than him. Ultimately, our times through this sector were almost identical, further showing that no one style is always best.

Dean’s Top Tips

One thing that impresses me most about Dean’s driving style is that he’s always working on it. And in his quest to keep his cornering speeds higher, he’s picked up a few bad habits — “not slowing enough to the corner apex and picking up the throttle too quickly”, he said — that he’s trying to correct.

These mainly show up in GT3 cars, which don’t have the same downforce levels as an Indy car and therefore can’t handle that style as well. He said that working on those two areas alone helped him gain almost a second per lap in a recent GT3 race week at Barber Motorsports Park.

Dean also shared a few pointers for getting up to speed in downforce cars.

“You want to run the widest possible arc through the corner to maintain the highest speed possible,” he said. Of course, this was clearly evident in his style compared to mine through the esses at Le Mans.

“Second is braking application,” he told me. “When you first apply the brakes, the car is at speed and will have the highest downforce, so apply maximum pressure. As your speed slows, so does the amount of downforce, so you need to bleed off the brakes correspondingly in order to prevent locking up the tires.”

This approach to the braking zones is a stark contrast to my own braking style, which I described in the previous post.

“This is a little different than other cars where threshold braking is based primarily on weight transfer. The open wheel cars are good for learning this technique as you have the visual cue of seeing the front tire lock up in addition to the feel and sound.”

Aero on Ovals

Just as a certain driving style is more suited to high-downforce road cars, different downforce packages on oval cars also demand specific styles. These differences have come to light in recent years with NASCAR’s changes to the Cup Series aero package, first adding downforce in 2014 and 2015 before removing it in 2016 and 2017.

The virtual representations of these cars in iRacing also received the aero updates, and they certainly affected my ability to perform well. On the blog, I previously described the struggles I had with the Gen6 cars when they had a high-downforce package. It demanded driving the cars deep into the corner and keeping mid-corner speeds higher, neither of which fits my style.

Not coincidentally, Dean performed at his best with this high-downforce package, picking up his only Power Series win at Kentucky in early 2016, just before that year’s real-world lower downforce package came to iRacing.

While I struggled in the first few races of that Power Series season, once the aero changes arrived, I was back on my game. In the seven races with the old aero package, my average finish was 6.7. In the ten races with the lower-downforce package, my average finish was 3.7, and that series of strong runs helped propel me to the championship.

That’s a big change, and all because of that strange, invisible force that rewards your faith in it and amplifies your advantage from it.

I still don’t trust it.