Watch most any sport and you’re likely to notice individual differences from player to player, whether it’s how they grip the bat, swing the club, or throw the ball. These differences exist in racing, too, although they’re often much harder to see with the drivers nestled within their cockpits, hidden by rollbars, custom-fitted seats, and other gear.

At the most basic level, driving styles come down to inputs: what drivers are doing with their brake, steering wheel, and throttle. As the other two posts in this series will discuss, some styles are better suited to certain characteristics, like driving with downforce, or to certain setup types, like driving a tight oval car.

However, by and large, there is no right answer for how to drive, other than “as fast as possible”. Well-matched drivers in the same car or series may use very different styles, or variations of the same style, to achieve a similar pace.

Like any skill, driving can be coached, and driving styles can evolve because of that. Personally, though, the basic mechanics of my style developed largely as a result of circumstance.

My Style

For many years, I raced with a Microsoft Sidewinder wheel and pedal set. It was a solid piece of hardware when my dad and I bought it nearly two decades ago, but over time, it became outdated and subject to plenty of wear and tear.

The greatest wear came when one of the two springs in the brake pedal broke in half. In a pedal that already didn’t offer much resistance, that provided even less, which meant the difference between minimal braking and full pressure was extremely small.

Even with plenty of experience using that pedal, I — or it — still wasn’t good enough to consistently brake late. My desk at the time couldn’t support a different wheel or pedal set, so I just made do with what I had. That meant braking earlier and getting back on the throttle earlier to maximize my exit speed.

That slow-in, fast-out style works well for stock cars and most road racing tin tops. Since that’s mostly what I was driving, my threadbare brake pedal wasn’t much of a problem. In fact, even when I upgraded to better pedal sets that would support later braking, I largely kept the same driving style.

In my experience, this is not a common or even an intuitive driving style. Braking late and hard seems to be a better way to maximize the time spent at high speeds and minimize the time at slow ones. For that reason, when people are trying to find extra pace, their first inclination is often to drive deeper into the corner.

While that can be a viable strategy when executed well, more often, it results in overdriving the corner, which means missing the apex and getting back to the throttle later rather than earlier. Even I am guilty of trying this sometimes, especially in downforce-equipped GT3 cars, and I almost always find that I’m faster with my more disciplined slow-in, fast-out style.

Braking

At least one Formula 1 driver in every generation, from Ronnie Peterson to Lewis Hamilton, gets bestowed the nickname of “last of the late brakers” for their ability to push their braking points as deep into the corner as possible.

I certainly will never be a candidate for that nickname. In fact, I’ve joked before that I’m more like the “earliest of the late brakers” since I generally get on the binders sooner than most of my competitors.

Going back to the origins of my driving style, braking has rarely been an opportunity for me to gain time. Instead, I try to get my braking done as soon as possible so I can get back to the throttle early — slow in, fast out.

That means braking is usually an exercise in weight transfer for me. Whether on road or oval, one characteristic of my driving style is using my initial brake application to get the nose planted, then backing off on the brake pedal as I approach the corner entry, with some occasional minor trail braking as I turn in.

This weight transfer is so important to me that I often use a dab of the brakes for corners where other drivers only lift off the throttle. The Blanchimont corner at Spa is a great example of this; it’s not quite flat-out in a GT3 car, so I typically tap the brakes before turning in to plant the nose and make the car a bit more settled through that tricky corner.

On ovals, my style is very similar. Even at high-speed tracks like Atlanta or Charlotte, I still tend to use a touch of the brakes entering the corner before coasting through the center and rolling back onto the throttle. Along with being a bit more fuel-efficient, this approach can help save the tires.

Steering

Steering isn’t only about how much (or how little) the wheel is turned; you often steer the car as much with the brakes and throttle as you do with the wheel itself. Great drivers are masters of this, and perhaps none are better in this department than the late Ayrton Senna.

His driving style was famous and truly unique, largely because of how he steered the car. Senna often used less brake entering the corner but, using a combination of the steering wheel and the throttle, still managed to get the car turned. By mid-corner, he often made severe steering inputs — for a left-hander, a brief jab to the left — and began pumping the throttle to force the car to rotate.

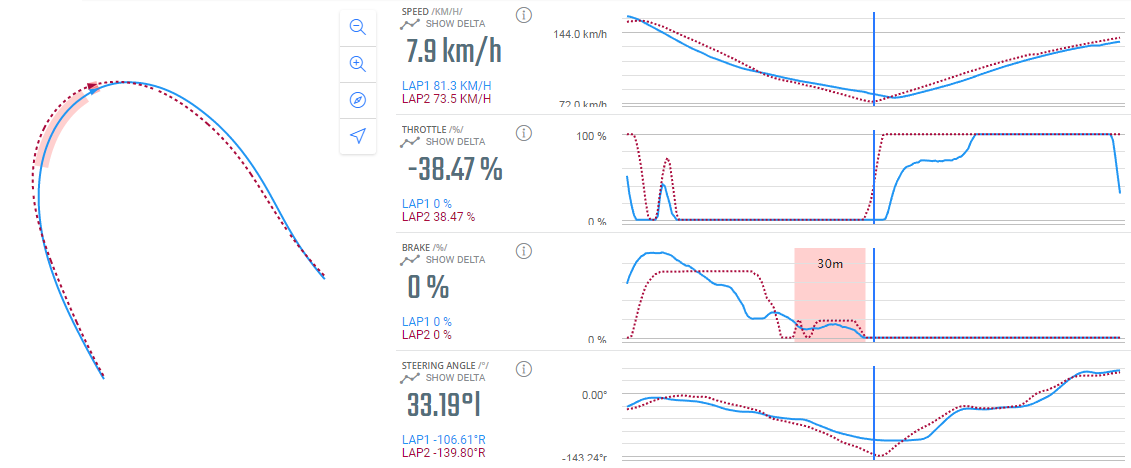

While few drivers have Senna’s talent to execute such a style, I have seen elements of it in drivers I’ve competed with. Namely, my teammate Karl Modig has a similar tendency to use a mid-corner flick of the steering wheel. That is evident in traces of our respective speeds and steering angles from the tight Bico de Pato corner at Interlagos.

In this particular sector, he made a much wider corner entry culminating in a sharp mid-corner right turn, using 30+ degrees greater steering angle than me to get the car turned sooner and get back to the throttle earlier. However, because my mid-corner speed was nearly 8 km/hr higher, we had identical times through this sector — evidence that there isn’t one correct driving style, but multiple ways to achieve the same result.

Karl’s big steering inputs often mean that he diamonds the corners to get the car to rotate. I have copied this technique in corners like Rivage — Spa’s 180-degree right-hander — and found success with it as well.

In general, though, I tend to have smoother steering inputs, rarely making sudden movements. Just as with braking, much of this comes down to having predictable weight transfer.

This approach can be particularly useful on an oval. In my earliest races driving the then-Nationwide Series car on iRacing, I would have good speed early in a run but fall off a ton by the end; in one race at Iowa, I had a line of a half-dozen cars behind me that I’d passed earlier but was eventually holding up.

After that race, another driver suggested that I try turning the wheel less. It was tough to consciously change that and it required other adjustments as well, like earlier braking and more mid-corner coasting, but in my subsequent oval races, I became more aware of it and was eventually able to make it a part of my driving style. That made me a much better driver when it came to maintaining long-run speed.

Throttle

On the surface, acceleration would seem to be the easiest input: Just hit the gas and go, right? That’s true for most cars, and yet throttle application may be my biggest area for improvement in terms of inputs.

Time after time when comparing against Karl, I’ve noticed that I’m far too hesitant in getting back to full throttle. While he is able to get on the gas 100% and stick with it, I generally ease back on the throttle as if I’m afraid of spilling the drink in my cup holder.

I have often attributed this aspect of my driving style to muscle memory from driving so many heavy cars, especially stock cars, that don’t turn very well and can’t handle the sudden rearward weight shift caused by a sudden burst of acceleration.

In addition, when trying to match Karl’s pace, I often find myself rushing back to the throttle too soon, which forces me to feather it for longer. Just as with braking later, trying to get back to the throttle earlier is a common tendency for drivers searching for speed, but it rarely pays off.

While it’s tempting to try to match Karl’s timing, I have to remind myself that he can get back to full throttle so soon because his high-energy but speed-bleeding mid-corner steering inputs set up a straighter, faster corner exit. I, on the other hand, have to wait for the car to finish rotating and roll onto the throttle more slowly.

It’s probably worth reiterating — if for no other reason than self-preservation — that my approach isn’t all bad. It does build up less heat in the tires and often means a more predictable balance throughout the corner, especially in a stock car. I fully admit, though, that I could gain a lot from adopting parts of Karl’s style when driving more maneuverable cars.

Putting It All Together

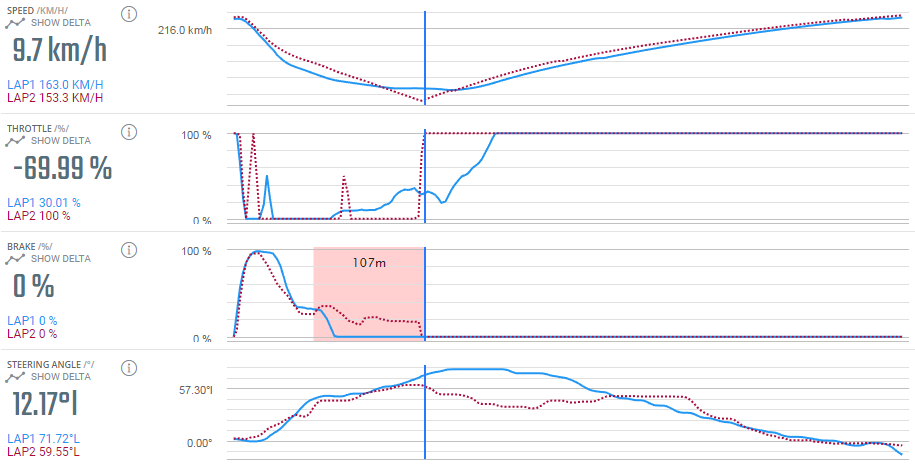

The differences between my and Karl’s styles are illustrated well in one corner: Pouhon at Spa. The double-apex left-hander requires precise braking, steering inputs, and throttle application, and it tends to highlight my flaws with each.

Karl uses maximum braking for less time than I do, which gives him greater entry speed. However, he also trail brakes for longer than me, so he bleeds off that speed and then some by the middle of the corner.

However, while he’s trail braking, he is also getting the car turned, all while using less steering angle than me. He pointed out that I tend to have more entry and mid-corner understeer than he does, largely because his inputs allow the car to rotate a bit more effectively.

The biggest difference comes with our throttle application. Once Karl has the car slowed and turned, he immediately gets back to 100% throttle and never wavers. Meanwhile, I feather the gas and get back to full throttle much later in the corner. By then, Karl is going nearly 8 km/hr faster than me. Not coincidentally, that’s where he makes up the most time. In this sector alone, he was nearly two tenths quicker.

Karl and I both use a slow-in, fast-out style, but his is a more optimized and aggressive version of it. By comparison, my style is smoother but more conservative, which may work well for cumbersome cars that don’t like braking, turning, or sudden throttle application, but it leaves a lot on the table in most other cars.

With that in mind, it’s probably no surprise that I’m almost constantly chasing Karl’s lap times. In fact, the running joke between us is that he’s always a half-second quicker than me, and if I manage to get within that gap, it’s up to him to find more speed.

Even disguised behind a computer screen, my driving style can’t hide; the telemetry and lap times tell all. And as racing drivers for the past 100 or more years have found, the differences often come down to inputs.